# of episodes

episode average

26

3.47

series Top 20

series Flop 20

2 episodes

1 episode

SEASON BEST

The Best of Both Worlds (I-II)

The Drumhead

The Wounded

Reunion

Night Terrors

SEASON WORST

Galaxy’s Child

Qpid

The Mind’s Eye

The Loss

Legacy

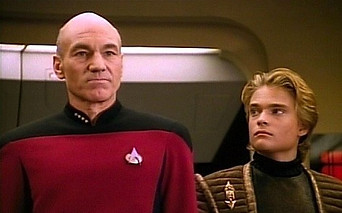

3.26/4.1 THE BEST OF BOTH WORLDS (I-II)

The Borg attack the Federation

and force Picard to collaborate.

SERIES TOP 20

This is universally considered the best episode of the entire show, and among the best in all of Star Trek’s 50-year run. I think this is for three reasons. For one, it subverts established narrative canons by turning a protagonist into an antagonist: seeing this for the first time during the original run was as big a shock as the Vader revelation in Star Wars. Second, it sets a new bar for TV science-fiction action epics, in terms of both budget and ambition: while future ST episodes would surpass this one with more money and better action (e.g., DS9’s “The Way of the Warrior” and VOY’s “Scorpion”), this episode did it first and did it best. Third, it was a huge gamble to leave viewers with an image of a Borg-assimilated Picard etched in their minds for months while they waited for a resolution: all we have to do today is insert the next disc, but back then the wait was significant, for it made the crew’s grief feel real to us as well. As for the script itself, there isn’t much to say that hasn’t been said already; even casual viewers have waxed poetic on this episode, so I don’t feel like I can add much. Instead, I’ll focus on three scenes that “make” the script for me, three moments that strike me at every rewatch:

(1) The parallelism between Guinan’s two scenes: the dialogue with Picard in Ten-Forward before the battle and the one with Riker in the Ready Room afterward. Her advice doesn’t change. She tells Picard that “life will go on” even if the Borg win, and then she tells Riker that letting Picard go is “the only way to save him.” Not only is this advice remarkably consistent, but in a sense, somewhat transcendentally, Guinan is talking to Picard both times: the first time to describe the loss and the second time to actualize it. This scene cements her role as the show’s moral compass.

(2) Data and Worf’s rescue of Picard from the Borg. The script is fairly common here, but the technical mise-en-scene is outstanding: from the visual effects to Ron Jones’ musical score, the scene has a movie feel and it’s entirely different from what we normally saw on TV in the 80s. Once more, later shows (especially DS9) would make high production value a regular occurrence, but this was definitely novel at this point.

(3) The battle of Wolf 359 doesn’t get a lot of attention aside from its instrumental value, but it’s significant for continuity. This is the first time that we see the Federation portrayed as vulnerable, a scenario that will become more common later as the franchise moved away from Roddenberry's utopianism and toward the fatalism of 1990s science-fiction. Wolf 359 is also pivotal to Benjamin Sisko’s backstory in DS9, whose pilot episode “Emissary” ties in to “The Best of Both Worlds” in an excellent and innovative way through the Sisko-Picard acrimony.

Picard returns to Earth to his brother's farm to cope with the trauma of assimilation.

4.2 FAMILY

Atypically for Star Trek, this episode shows a remarkable continuity by tackling the big question before it becomes the elephant in the room: how has the Borg abduction changed Picard? The answer we get is satisfactory on its face, but way too under analyzed in a dramatic sense. Much of the episode is wasted with two forgettable story arcs: Picard's adversarial relationship with his brother, who is written with no subtlety whatsoever; Worf’s awkward parents; and a holographic message from Jack Crusher recorded when Wesley was an infant. All three detract from the episode’s eventual acme: Picard’s breakdown and much-needed humbling. It’s a fine line that separates filler from buildup, and the script has too much of the former and not enough of the latter. By the time the reckoning comes, it’s over far too soon and immediately forgotten. The scene itself, the fist fight in the vineyard, is well scripted and powerfully acted by Stewart, but that’s not enough. Still, it’s so good to watch that it earns the episode a higher rating than it would have otherwise. This episode is also important for continuity, as Robert’s and Rene’s fate is the driving emotional engine for Picard in Generations. Likewise, it provides a welcome insight into the not-so-futuristic future of some Earth communities, which DS9 will explore in even better depth.

WATCH FOR CONTINUITY

4.3 BROTHERS

Data's homing beacon leads him to meet his creator, Dr. Noonien Soong.

WATCH FOR CONTINUITY

Two sets of brothers and two story arcs with nothing in common, save for a feeble justification at the end (“brothers forgive each other”) and to provide a contrived reason to isolate Data from the Enterprise. On the upside, this allows the writers to construct a magnificent action sequence for Data’s escape, which is every bit as entertaining as the ones in S3’s “The Hunted.” On the downside, so much of the episode is wasted on secondary aspects that turn out to be irrelevant to the main plot, which as a result feels grossly undervalued. No doubt this was done in part to minimize the three-way interaction among Data, Lore, and Soong, all three of whom are played (and wonderfully) by Spiner. Still, the result is an episode that drags its feet in the scenes on the ship and that feels hurried in the scenes on the planet. Despite all this, the Data-Lore-Soong triad is very well written, and this episode is a crucial turning point in Data’s personal story. The “emotion chip” idea starts here, and it’s a while before Data would find it again (and longer still for him to use it, much to his own detriment, in Generations). The discussions on immortality, while slightly predictable, are an excellent means to explore Data’s own sense of mortality, which is sadly crucial to the future development of TNG. Overall, this episode is a mixed bag, but its importance for continuity makes it a must-watch.

The Enterprise find a human survivor on a crashed Talarian ship.

4.4 SUDDENLY HUMAN

An average alien-of-the-week installment with a trite story: kid doesn’t know who really loves him, acts out because he’s confused, and finds himself eventually. We have seen it all before. On the other hand, the expected happy ending doesn’t take place, as the boy returns to “the only home he has ever known,” the Talarian ship. Alas, for this twist to work there should have been a more thorough discussion of nature vs. nurture and the individual-group relation. The script is pretty shoddy when it comes to those (by contrast, VOY’s “Ashes to Ashes” would do a better job), preferring to focus instead on the boy’s emotional needs and Picard’s discomfort in a parental role. The script lacks depth as a result of this choice. Relatedly, the assault on Picard is a big miss. He has been stabbed before and has just been assaulted by the Borg, two events that contribute massively to his mortality... yet this one assault, which seems every bit as serious, is brushed off in the span of a one-minute scene. That doesn’t fly. Overall, a decent episode with a few interesting scenes and good guest performances by Chad Allen and Sherman Howard, but nothing more.

SKIPPABLE

4.5 REMEMBER ME

Beverly is trapped in a parallel reality where the crew is disappearing.

SKIPPABLE

An above-average tech puzzle (a warp experiment gone awry) with a below-average secondary plot (“if you fear missing your loved ones, you’ll create a reality where they disappear”). Obviously, the script stumbles comically whenever it attempts to take its premise seriously, and McFadden’s usual overacting doesn’t help. The result is a half-episode, where the audience is forced to disregard the psychobabble in favor of the technobabble. Fortunately, there are some positives too. The return of the Traveler is well written and moderately intriguing, as are many of the scenes in Beverly’s alternate reality, with the gradual disappearance of the crew and the increasingly absurd conversations with the computer. The only major problem with the technical side of the story is that it shouldn’t have taken so long to figure it out: only three people were in Main Engineering when the shit hit the fan, and only one of them has a problem with reality. Hence, there’s a problem with her, not with reality. Elementary, dear Data. In the end, this is an average episode with fairly balanced highs and lows.

The crew become entangled in a clan war on Tasha Yar's home planet.

4.6 LEGACY

S3’s “Yesterday’s Enterprise” was TNG’s first of many attempts to walk back their Really Big Mistake of killing off Tasha Yar, and that episode was a resounding success. Their second try is less so. This predictable action drama set on Tasha’s lawless home colony is based on the premise that the crew miss her so much that they would gladly deceive themselves by seeing Tasha in her long-estranged sister. That might be just as well, but that sleight of hand doesn’t work nearly as well on the audience. Ishara is a wholly unconvincing character, who just is not well written enough to sell her (despite Beth Touissant’s... presence). While her would-be friendship with Data has some good moments, such relationships are only as good as the lasting change they effect on the series regular; that’s definitely not the case here, as Data doesn’t seem to learn anything that he hasn’t learned before. It is also hardly believable that such an advanced entity with decades of military service would struggle with the basic concept of “trust.” So even though the episode is watchable and occasionally entertaining (because TNG’s writers haven’t produced a single lemon in the show’s middle three seasons), it is too far from ideal to be considered “good” in any charitable sense of the word.

SKIPPABLE

4.7 REUNION

K'Ehleyr returns with her and Worf's son amidst Klingon political turmoil.

SEASON TOP 5

Another excellent chapter of Worf’s family history and of the Klingon political intrigue story arc. This is the ideal sequel to S3’s “Sins of the Father,” and it paves the way for the upcoming two-part cliffhanger “Redemption”; and just like those episodes, this one too succeeds in intertwining beautifully the personal and the political. After accepting dishonor for Duras’ sake, Worf finally takes revenge and kills Duras in combat, much to everyone’s cheers. This hands Gowron the leadership of the High Council, a decision that will have massive repercussions for the next decade of Star Trek. Here Robert O’Reilly’s performance as Gowron is overstated and frankly a bit caricaturing, but over time he will tone it down and deliver one of the franchise’s most charismatic alien leaders. But once more it is K’Ehleyr who steals the show, thanks to Suzie Plakson’s forceful interpretation. Sadly this is the character’s last appearance, but thankfully not the actor’s. As for Alexander, while he will be a sore spot in the coming seasons due to silly plots and bad acting, in this script he works well as a token of parental discussion between Worf and K’Ehleyr. In conclusion, this highly charged episode works well on all fronts, adding to the high quality of the Klingon epos imagined by TNG’s writers and so well rendered on the small screen.

Riker awakens in the future with a 16-year memory gap.

4.8 FUTURE IMPERFECT

This sort of episode is always a big gamble. Surely we know that Riker didn’t just skip 16 years, so something must be up. Time travel? Holo-program? Deception? Either way, the script better be very good, or we aren’t going to care enough to stick around for the big reveal. This one is indeed good, with the occasional ups and downs. It has two selling points. One is the specific future that it proposes: consistent, logical, and just odd enough to keep arousing our suspicion at every turn. But truly, if it hadn’t been for the Minuet mishap, all of it would have made very good sense, to us and therefore (eventually) to Riker. The second asset to this episode is the dual resolution. It’s hard to pull off a Matrix-like “this is all part of a computer simulation” big reveal, but this script does it twice, both convincingly. The second one is fully shocking, as the Romulan interrogation scenario was a very believable explanation. The eventual “real” level of reality, with the stranded alien kid and the neural detectors, is a little lackluster by comparison, but it does tug at the heartstrings in all the right ways. Perhaps the episode’s worst sin is that it doesn’t have much to say beyond itself. The “imperfect" future doesn’t really teach Riker anything --- nor, to be fair, was it ever meant to. So while the episode is good, it is "just” a fun adventure. (Fun fact: VOY S6’s “Living Witness” is the only time a far-future scenario turns out to be real, though with no consequences on the show’s timeline).

WORTH WATCHING

4.9 FINAL MISSION

Picard and Wesley are marooned on an arid planet with no water.

WORTH WATCHING

Wesley’s last episode as a series regular is also his best: a carefully written survival tale that allows him and Picard to finally grow closer. The script does a good job tying back the loose ends from previous seasons into a series of insightful conversations, culminating in a true father-son moment. The survival story itself is intelligently crafted, with reasonable concerns and an intriguing puzzle. However, it is upsetting that the Enterprise would be taken out of the picture with such a weak pretext that has nothing to do with the main story arc. They could have easily joined the search and been hindered by some technical problem, and it would have felt more genuine.

The ship runs into two-dimensional beings and Troi loses her emphatic powers.

4.10 THE LOSS

An occasionally awkward, slow, and simplistic look at the importance of empathic powers for Deanna and Betazoids in general. The script is undecided on what it wants to say, jumping around quite clumsily from disability to career ethics to inter-species communication. The idea of two-dimensional space-faring beings is intriguing, and it is well devised and resolved. However, it is insulting that a Starfleet captain would not call for the abandon ship when faced with certain death. Ultimately, this episode is best at showing how the Riker-Troi relationship dances on the line between friendship and romance, a topic that will become more important in coming seasons.

SKIPPABLE

4.11 DATA’S DAY

Data describes a not-so-typical day aboard the Enterprise.

WORTH WATCHING

An insightful and hilarious tale on the lighter side, cleverly crafted as a letter to Commander Bruce Maddox, who in S2’s "The Measure of a Man" had tried to argue that Data was not alive. It allows us to get a much-welcome look at ordinary life aboard the Enterprise, as well as provide a genuine growth opportunity for Data. The script is peppered with memorable scenes, from the hilarious tap dancing lessons to the Keiko-O’Brien wedding. Each one of Data’s interactions with the crew says something important about his analysis of the human experience, and his relation to each officer is carefully discussed while remaining fully in-character --- not an easy feat after four seasons. Moreover, the plot that would normally be the main story arc is relegated here to a secondary role, both in terms of screen time and because it serves the purpose of Data’s main story. And despite all that, it still ranks among the better Romulan spy stories, with the traitor T’Pel and a transporter accident. If we must find a downside to this episode, is that Keiko is introduced too hastily: we know and love O’Brien, and suddenly he’s marrying a character we have never seen before, but who somehow Data knows well enough to pose as the “father of the bride”? It’s a pretty hard sell, though in the end it works thanks to Rosalind Chao’s charismatic portrayal of Keiko, who will become important later in the show and of course in DS9.

A Federation captain goes on a rampage to kill Cardassians.

4.12 THE WOUNDED

A fantastically written psychological thriller on radicalization, war, and diplomacy, with a strong guest performance by the iconic Bob Gunton and the first important role for O’Brien. These themes would become cornerstones of DS9, and to an extent of VOY and ENT, but they are relatively rare in TNG, and here we get our first real look at them. The Cardassians are also introduced, the species with whom these themes are most closely associated. Rightfully, though, the script focuses on the one human character whose Cardassian war crimes supposedly turned into a villain, a theme that would be explored further later in TNG (e.g., S5’s “Ensign Ro”) and DS9 (e.g., S1’s “Duet”). Maxwell’s extremism is juxtaposed with O’Brien’s reasoned moderation, and it is the latter who serves as the episode’s moral compass: scarred by war, he distrusts Cardassians but he has succeeded in not turning his war experience into self-consuming hatred, precisely what Maxwell (who lost his entire family) hasn’t been able to do. The final scene between the two, with the war song, is quite heartfelt and caps off the episode ideally. Perhaps in preparation for DS9, the script remains ambiguous about whether Maxwell was right about the Cardassians’ rearmament. It is to the writers’ credit to be able to deliver a nuanced drama with no clearly defined heroes and villains, except of course for the stability of Picard’s strong moral universalism that drivers most TNG’s plots.

SEASON TOP 5

4.13 DEVIL’S DUE

A woman claims that she is the devil and that a planet belongs to her.

WORTH WATCHING

A wildly entertaining episode that ranks among the most original in all of Star Trek. The notion of con artistry isn’t explored a lot in the series, which makes sense given its post-capitalist setting, but it proves to be funny and intriguing both times (this episode and the somewhat less successful VOY S7’s “Live Fast and Prosper”). Despite succumbing to some of the idiosyncrasies of procedural courtroom drama, which for some reason is entertaining to American audiences, the script is witty, cunning, and never strays from the point. The final “gotcha” moment, with the revelation of the true source of Ardra’s powers, is particularly funny. But there’s more than just comedy here. The script makes a lucid argument about the social power of self-transformation, even if subtly motivated by a latent fear of retribution. Indeed, despite the lighthearted tone one might call this a socially concerned episode, especially with regard to environmental issues, as there are many in TNG and all of ST. Still, it remains memorable primarily because of Ardra’s fascinating character (excellently portrayed by Marta Dubois) and because of the flashy visual effects.

The crew suspect they were unconscious for a day and that Data is responsible.

4.14 CLUES

This episode has all the makings of an engrossing mystery: eerie, well paced, and with a genuinely stunning resolution. Hints are dropped in just the right way, and the debates that ensue are logical. Although it’s made clear early on that Data is the “villain,” surely we know that he must have good reasons for what he’s doing, and thus his character remains likable and his reactions sensible (also thanks to Spiner’s great subtlety). Indeed, it’s entertaining to see how the accumulation of evidence slowly erodes his argument, eventually forcing the final confrontation with Picard. If anything, if there’s an objection to be raised it’s that Picard’s fateful order is far too vague, so much in fact that it strains our disbelief: a few simple additions, such as to rescind the order in the exact circumstances that did in fact occur, would have avoided the entire incident. But one may forgive this and write it off to poetic license. After all, the episode’s top strength lies in its depictions of just how many ways there are to tell the passage of time. In this, the writers excel by choosing a clear focus and never straying from it. The ending is exciting and well orchestrated, if a bit surprising: the solution is to simply do it all again, with relatively little guarantee that this time all will go well. But that too is fairly realistic, given the circumstances, and it works quite well in the episode.

WORTH WATCHING

4.15 FIRST CONTACT

The crew contact an alien species on the eve of its first warp flight.

WORTH WATCHING

This episode is surprisingly naive for a show centered on discovering “new civilizations.” The rational for Starfleet’s first contact procedures is greatly underanalyzed. For example: Why make first contact before an actual warp flight has taken place? Surely Riker precipitated the issue, but Picard is clear that this is a standard first contact scenario. In some way, this will be rectified in First Contact the movie, where the Vulcans only land on Earth after Cochrane’s flight. This is but one of several inaccuracies here. Another is the depiction of Malcorians as a whole. For a warp-capable society, they are remarkably backwards in scientific matters. While no doubt a particular history is possible that would lead to this, we are not told any of it, so Malcorian society feels incomplete. Despite all this, the resolution is well written, thanks to an excellent conversation on the nature of social progress. The ending is particularly clever, as a botched first contact is the only way that this story could have ended. The reluctance to go “too far too fast” is well portrayed, not so much because the writers intend to make a socially conservative point, but because it lives up to the spirit of the Prime Directive: a civilization must be ready for the advanced citizenship demanded by an interstellar community, and the Malcorians clearly aren’t... just like XX century humans aren’t, which is the big so-what for the audience. So despite significant narrative drawbacks, this is a thoughtful episode that provides some mature reflection prompts.

A space-born life-form attaches to the Enterprise and saps its energy.

4.16 GALAXY’S CHILD

If we go by this episode, Geordi La Forge is the creepiest man in space. It’s not so much about the holographic Dr. Brahms, though it’s that too: the script conveniently hides the fact that Geordi and Leah’s hologram got physical, and if she had known that probably she would have been a lot less conciliatory. No, what’s troubling is that Geordi expects her be a romantic partner, she turns him down, he gets mad, and she ends up apologizing for hurting his feelings! Take-home point: women must be emotionally available according to men’s fantasies, and they are to blame otherwise. The entire relationship between Geordi and Leah is literally painful to watch, and it ranks high among ST’s worst sexism (until VOY S4’s “Retrospect,” which argues that women should think twice before reporting assault... for men’s sake). The only redeeming presence here is Guinan, who warns Geordi that he’s being a creep; but all that is brushed aside when the burden of civility is placed entirely on Leah, because of course the series lead cannot be in the wrong and it’s the guest star that needs to be put in her place. This subplot greatly sours the main plot, which would have been good on its own accord. While this isn’t the first time that TNG toys with the idea of a space-faring life-form (S3’s “Tin Man”), here the writers can explore the concept in more detail. Both the birthing and the weaning scenes are well written, and despite the cringe-worthy CGI they hold up well today. But the shameful morality of the Geordi-Leah plot ruins all of that, and the episode would score significantly higher otherwise.

SERIES FLOP 20

4.17 NIGHT TERRORS

The crew salvage a ship whose crew members killed each other.

SEASON TOP 5

Star Trek rarely ventures into thriller/horror territory, but when it does it is usually successful. This remains one of the best episodes of this sub-genre, with a delightfully eerie setting that properly conveys the sense of deep isolation and a genuinely creative sci-fi (re)solution. The premise is far from original: the Enterprise is stranded in a space rift next to a ghost ship whose crew members inexplicably murdered one another. But the discovery of the reason why is actually innovative: a telepathic distress call from an alien ship, trapped on the other side of the space rift, is causing a disruption of REM sleep frequencies; thus, naturally, Troi is tasked with communicating with them. The mystery unfolds slowly and deliberately, with increasingly creepy incidents and a remarkably realistic portrayal of sleep deprivation-induced paranoia, from increased aggressiveness to Crusher’s bone-chilling hallucination in the morgue. The scene where Troi and Data attempt to figure out the content of the message to send the alien ship is an excellent exercise in inductive reasoning. So despite an occasionally formulaic execution (e.g., Troi’s dream scenes are unnecessarily repetitive and drawn out), the episode works extremely well and remains memorable, in no small part due to its uniqueness.

La Forge's old crew are transforming into aliens and disappearing.

4.18 IDENTITY CRISIS

It was quite a gamble to follow up on “Night Terrors” with another dark episode, but it paid off. And unlike in that episode, here the premise is innovative: an alien species that reproduces by implanting spores in an unsuspecting host, who is then drawn to the aliens’ home planet later in life. The script ably intertwines a cold case-like investigation with a medical mystery, also thanks to the introduction of a solid supporting character in Susanna Leijten. The eventual reveal of the alien design is also effective, as it manages to be unsettling without being ridiculous or unbelievable. But it is Geordi’s holodeck investigation that steals the show here. As in S3’s “A Matter of Perspective” and S6’s “Schisms,” the writers seem to understand the forensic potential of the holodeck technology and put it to good use. Geordi’s discovery of the missing shadow is greatly entertaining, and a capable use of art direction and lighting make the scene even eerier than the eventual resolution on the planet in the ending. Overall, the episode certainly doesn’t rewrite the book on sci-fi horror, but it adds a solid and entertaining page to it.

WORTH WATCHING

4.19 THE NTH DEGREE

Barclay's brain is enormously augmented by an alien computer.

SKIPPABLE

“I’m afraid I can’t do that, Captain.” This jumbled mixture of Flowers for Algernon, Contact, and 2001: A Space Odyssey could have been great, but is confusing and soulless. The premise is solid: a species explores space via probes that instruct sufficiently advanced sentient beings to build a new transportation system, tunneling them to the galactic core for a rendezvous. It is so grandiose, in fact, that it can’t possibly be analyzed thoroughly in 44 minutes; and even less so when the subplot of Barclay’s social life takes up so much space. The ending is especially infuriating: “after spending ten days” with the aliens, the Enterprise just returns home. No mention of the massive technological strides that were just made, nor of the content of those ten days in which, presumably, much was learned from a far superior species. What did they know? Did they feel like sharing? How else are they involved in galactic matters? Do they too have a Prime Directive? Nothing at all, save for a meager “how much do you remember?” for Barclay... as if he had been the protagonist all along. The episode is enjoyable, but it bites off so much more than it can chew. Nor is this the last time that TNG does this: S6’s “The Chase” reveals the origin of all galactic life (!!!) with a half-assed script. Thankfully, VOY would be much more careful with such big-picture questions (e.g., S4’s “The Omega Directive” and S6’s “Blink of an Eye”).

Q traps the crew (and Vash) in a fantasy recreation of Robin Hood.

4.20 QPID

Historical fictions in Star Trek are hit and miss, from TNG’s excellent Sherlock Holmes to VOY’s awful Fair Haven. This one is somewhat in the middle. On the positive side, the crew are actually funny as Robin Hood and his gang, including some memorable gags: “Sir, I protest! I am not a merry man!” On the other hand, the entire scenario is clearly concocted only for the purpose of bringing Vash and Picard together and eventually break them up. And while that may be passable as a pretext, the problem is that Vash is thoroughly uninteresting: artless, predictable, and with nothing to say about the series regular that she interacts with (which is the only purpose for a recurring guest on a TV show, after all). Thankfully, S6’s “Lessons” would do a much better job at introducing a relevant romantic partner for the captain. As for Vash, sending her off with Q is poetic justice: useless together ever after. Still, despite the near-total inanity of the plot, the episode is a fun watch, perhaps precisely because it has nothing to say or do.

SKIPPABLE

4.21 THE DRUMHEAD

The suspicion of a Romulan spy on the ship starts a witch hunt.

SERIES TOP 20

“That’s how it starts.” This magnificent theatre piece is a master class in surveillance politics, constitutional law, and the facile allure of an exclusionary fascist mentality. The script uses Picard as a canary in the coal mine, a stalwart of justice in the face of a rising jingoism. It evokes a specter that we have seen in endless news cycles since the McCarthy era. Picard’s final speech to Worf lucidly analyzes how easy it is for the specter to resurface in even the best circumstances, such as Star Trek’s liberal utopia. In addition to being educational for the audience, this is a much-needed commentary on the politics of a show that are quite literally too good to be true. Surely the Federation isn’t an idyll, and this sort of incident is precisely what one would expect in what is for all intents and purposes a galactic empire. The episode is also excellently realized beyond its narrative merits, with great pace, a somber musical score by Ron Jones, and masterful performances by Stewart and special guest Jean Simmons. In fact, the conversations between Picard and Satie have an awe-inspiring clash-of-titans feel, and it’s no surprise that so much of the plot hinges on them. However, it’s Worf’s role that is pivotal: whereby Picard personifies justice and Satie jingoism, Worf represents the everyman, all of us who are caught in the ideological maelstrom. By first aiding Satie and then coming to his senses, Worf is every patriot whose fervor betrays a fundamental weakness of morals. And while this may be slightly out of character for him, it serves the plot extremely well and rouses us to the true danger of political paranoia: that it may corrupt those we consider above reproach, such as Worf. This is one of those episodes that stay with you for a long time, and which unfortunately remains relevant in the United States decade after decade. It figures regularly in various “best of Star Trek” rankings, and it is also a cornerstone of all my political philosophy and political science classes.

Lwaxana falls for an alien about to commit ritualistic suicide.

4.22 HALF A LIFE

A compelling analysis of mortality and moral relativism through the lens of a genuine dilemma. The script ranges from considerations on the nature of social utility to observations about family, social mores, and elder care, all without missing a beat. Lwaxana Troi, until now a caricature character with little to say, acquires a surprisingly deep dimension in this episode, which adds much subtlety and richness to her texture (S7’s heartbreaking “Dark Page” would build on this, too). The script’s central premise is analyzed carefully and in detail: should the elderly commit suicide before they become a burden on society? Both sides are given fair hearing and present valid arguments, from the idea that children should take care of their parents as they were taken care of, to the idea that one’s debt to society goes beyond one’s individual desires or utilitarian contributions. The result is an hour of intelligent debate, though tinged with occasionally overstated drama. The resolution is predictable for a Star Trek episode, but nonetheless reasonable and entertaining. David Ogden Stiers excels in creating a three-dimensional character for Timicin, and Majel Barrett is as great as usual. Fun fact: Michelle Forbes, later of Ensign Ro fame, appears here in a small role as Timicin’s daughter.

WORTH WATCHING

4.23 THE HOST

Beverly falls for a symbiotic alien whose host body dies in an accident.

WATCH FOR CONTINUITY

The invention of the Trill may have taken place in the middle of TNG, but it had far-ranging consequences on DS9. It’s a deeply fascinating species, though many of its characteristics would change over time. As for this episode, the decision to implant Odan into Riker is far too cavalier, with no debate of expected outcomes or theoretical issues. Much of the subsequent drama could have been avoided, or at least lessened, by a more careful deliberation in the first instance. Still, that bit of poetic license doesn’t diminish the impact of the script, which is entertaining and well acted by Frakes and McFadden. The romance that ensues between Crusher and Riker is too awkward to be effective: a much better move would have been to implant Odan into Picard and discuss how the symbiont and the host interacted, and thus whether it was Picard or Odan who was in love with Beverly: now that we would have loved to watch! Also on the negative side is that the ending reeks of politically correct homophobia: a fully heteronormative narrative is performed as usual, a straight person feels a little bad about it, and in the end they suffer no consequences. This definitely ruins the ending, not because Beverly should love Odan’s female host, but because an excellent opportunity is missed to discuss the roles of sex and gender in romance. Beverly’s little speech (“our inability to love”) doesn't make it better, and if anything testifies to the writers' unwillingness or inability to fully analyze the issue.

Romulans brainwash La Forge to assassinate a Klingon diplomat.

4.24 THE MIND’S EYE

The premise is innovative and engrossing: the Romulans abduct La Forge and brainwash him to assassinate a Klingon ambassador in hopes of disrupting the fragile peace between the two superpowers. But the resulting episode is bland and predictable, with few thrills and way too much procedural filler that’s supposed to build up tension and instead brings boredom. La Forge’s scenes aboard the Enterprise post-conditioning suffer from the same problem that earlier TNG episodes also incurred: the audience knows that since this character isn’t acting on his own volition, none of his actions will matter for his development after the end credits, and therefore we feel like we’re wasting our time.

SKIPPABLE

4.25 IN THEORY

Data initiates a "romance program" with a heartbroken crew mate.

WORTH WATCHING

The episode’s premise is valid and I can see why it was green-lit: what if Data dated someone? His fling with Tasha Yar in the show’s horrible second episode (S1’s “The Naked Now”) doesn’t really count, so this is his actual first time. His chosen counterpart, Lt. D’Sora, is a perfect fit, and she’s played with verve and nuance by Michele Scarabelli. The episode goes exactly as one may anticipates from the previews, with Data going through increasingly awkward attempts at impersonating human feelings: for all the show’s pretense that he is becoming more human, becoming a better impersonator is what he actually does (as do most humans as they mature, one could well argue). The resulting relationship is entertaining, at times laugh-out-loud funny, and at times sweetly heartbreaking. The conclusion is especially bittersweet, as the only inevitable ending is that Data was Jenna’s rebound and that he’ll remain alone. The fact that his feelings cannot be hurt doesn’t make it easier for the audience, whose projected feelings do ache. But perhaps this episode’s most important contribution to TNG is in the continuity of Data’s character development. Seasons 6 and 7 all but abandon the awkward-android-asking-what-words-mean arc, and instead portray Data to know almost all there is to know about human emotions... except the subjective feeling of actually having them.